Het jaar 2020 heeft ons tot op het bot geschokt. Tijdens de COVID-19-crisis werden alle vastgoedmarkten getroffen, maar één markt in het bijzonder wist goed te overleven; de woningmarkt.

Het jaar 2020 heeft ons tot op het bot geschokt. Tijdens de COVID-19-crisis werden alle vastgoedmarkten getroffen, maar één markt in het bijzonder wist goed te overleven; de woningmarkt. Volgens onze gegevens blijven de huizenprijzen stijgen, wat leidt tot enkele vragen. In deze serie analyseren we de woningmarkt; is er een sprake van een bubbel of is er nog ruimte om te groeien?

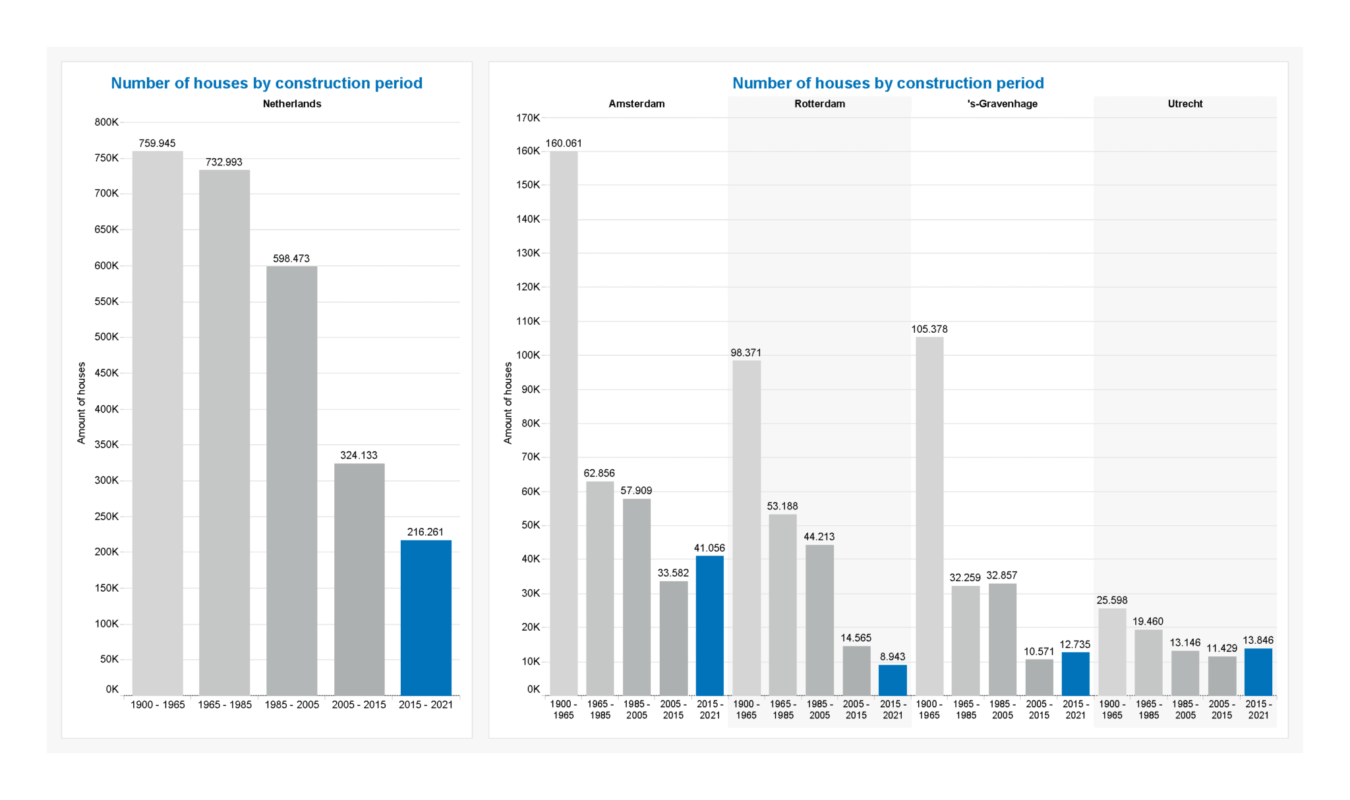

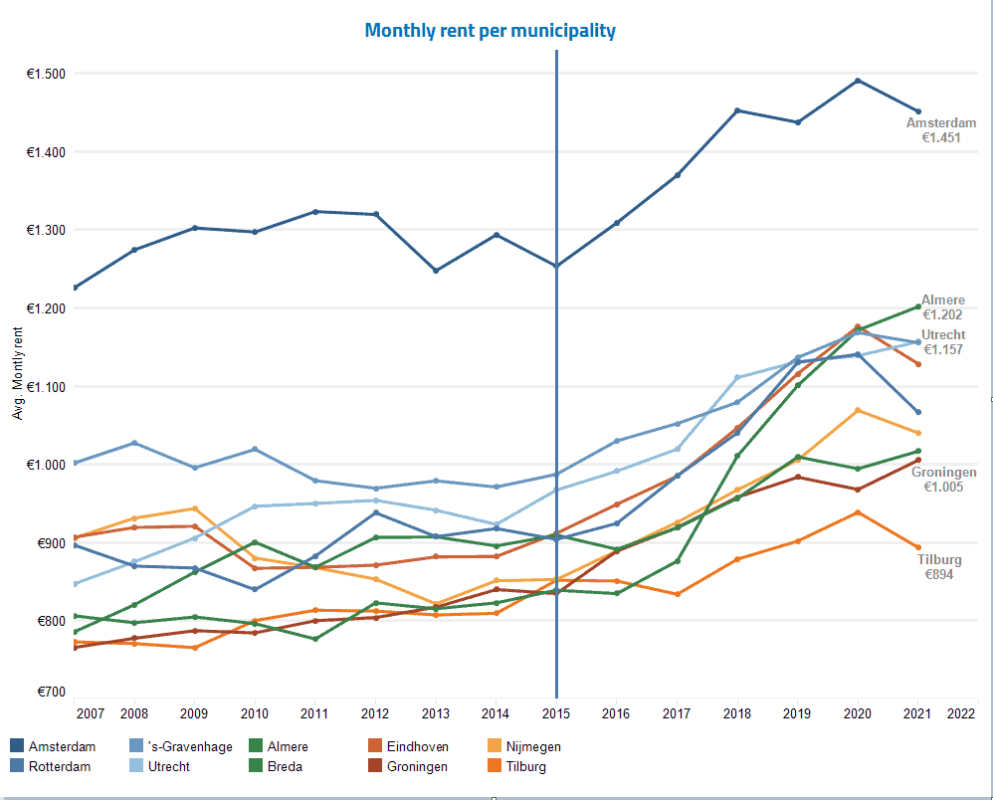

In onze laatste update onderzochten we de betaalbaarheid van de huurwoningen in Nederland. In deze update werd heel duidelijk dat de vierkante meterprijzen de afgelopen jaren enorm zijn gestegen. Dit is met name het geval voor de grote steden in Nederland. Hier krimpt de woonruimte en stijgt de huurprijs.

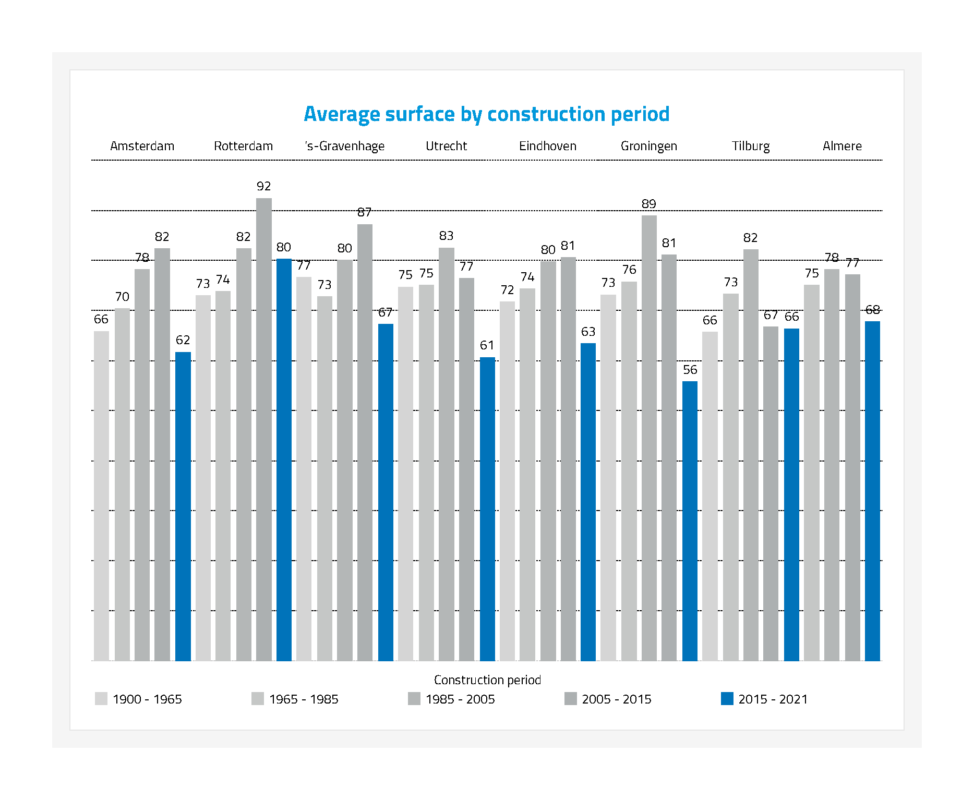

Sinds oktober 2015 wordt de WOZ-waarde van een huurwoning meegenomen in de bepaling van de huurprijs op basis van het woningwaarderingsstelsel. Het doel hierachter is om tot een huurprijs te komen die beter past bij de economische markt voor huurwoningen. De locatie van een huurwoning wordt hierin meegewogen waardoor het belang van andere woningkenmerken minder groot wordt bij de huurprijsbepaling. Waaronder de oppervlakte. Dit is duidelijk terug te zien in de keldering van het gemiddelde oppervlakte in bovenstaand figuur. Met name in de grote steden, waar de WOZ-waarde bovengemiddeld is, zien we dat de woningen steeds kleiner worden.

De woningmarkt kenmerkt zich door hoge verkoop- en verhuurprijzen die het resultaat zijn van een woningtekort, lagere rendementen en hogere bouwkosten. Nieuwbouw toevoegingen (op de huurwoningmarkt in de grote steden) worden niet gebouwd naar gelang de woonbehoefte maar naar het budget van de doelgroep. Zolang de huurprijzen per vierkante meter stijgen dienen de woningen kleiner te worden gebouwd om de beoogde doelgroep aan te kunnen trekken.

Dit beïnvloedt de samenstelling van de inwoners in de grote steden. Het is niet voor alle doelgroepen weggelegd om kleinere huisvestingen aan te nemen, waardoor er een trek uit de stad ontstaat. Denk hierbij aan het verdwijnen van lagere inkomensklassen ten behoeve van hogere inkomens. Maar ook aan gezinnen die behoefte hebben aan meer woonruimte. Dit lijdt tot gentrificatie in de stad. De potentiële doelgroep voor (micro-)appartementen is beperkt tot eenpersoonshuishoudens en koppels zonder kinderen die daarnaast ook de stijgende huurprijzen moeten kunnen betalen.

De uitbraak van COVID-19 had gevolgen voor de levensstandaard. De voorzieningen in grote steden maakten voor COVID-19 crisis een kleine leefruimte draagbaar. Dit geldt vooral voor jongeren die meestal onderweg waren of buiten aten om mensen te ontmoeten. Dit was tijdens de pandemie heel anders. Het wonen in de stad heeft hierdoor een heel andere betekenis gekregen.

Er moeten woningen gebouwd worden, maar voor wie?

Doelgroep gestuurd bouwen op basis van data, nodig Watson+Holmes uit en we brengen de ideale fit voor het project in kaart.

2020 has shocked us to the core. During the COVID-19 crisis all real estate assets were hit, but one asset in particular managed to survive very well; the housing market. According to our data, housing prices continue to rise which led to some questions. In this series we analyse the housing market and to which extend we note a housing market bubble or whether there is still room to grow.

In our last update we investigated the affordability of the rental houses in the Netherlands. In this update it became very clear that the square meter prices increased tremendously over the recent years. This is predominately the case in the big cities within the Netherlands. Here the living space is shrinking while the rental price continues to grow.

Since October 2015 the value of property is included in the determination of the rent based on the home valuation system. The aim was to determine rental prices which are better suited to the economic market for rental housing. The location of a rental house is related to this, so the importance of other housing characteristics became less important for the determination (like the surface). This is clearly reflected in the decrease in the average surface. Particularly in the large cities, where the value of property is above average. Here rental houses become smaller and smaller.

The housing market nowadays is characterized by high transaction- and rental prices, which are the result of a housing shortage, lower returns and higher construction costs. New-build additions are not built according to housing needs, but according to the budget of the target group. As long as the rents per square meter rise, the houses must be built smaller in order to attract the intended target group.

This effects the composition of the population in the big cities. It is not suitable for all groups to accept smaller houses. Think of the disappearance of lower income groups in favour of higher income groups. But also about families who need more living space. This leads to gentrification in the city. The potential target group for (micro) apartments is limited to single-person households and couples without children, who also have enough income to pay the rising rents.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 virus affected the standards around living. The amenities in big cities made a small living space acceptable. Especially youngster who were mostly on the go or eating outside meeting people. This has been tremendously different during a pandemic. Which gives living in the city a completely different meaning.